Lori Burton tells her story — and writes another love song for her husband and soulmate Roy Cicala. The video (below) is from the fateful Arbors sessions that led to Roy leaving A&R and joining Record Plant.

Lori Burton tells her story — and writes another love song for her husband and soulmate Roy Cicala. The video (below) is from the fateful Arbors sessions that led to Roy leaving A&R and joining Record Plant.

Roy Cicala and I met when I was 14 years old; we were childhood sweethearts. I was a singer. My father was a musician. And Roy was very good at anything involving electronics. He built a car, a ’32 Roadster with a Chevy engine in it. He did some things that were so incredible. But he was very quiet about his talent; he wouldn’t be a guy who would walk in a room and command attention. He was shy, but he was very talented.

Since I was a singer, my father decided to take the basement of our house in New Haven and turn it into a recording studio. Roy and I got even closer once we built that studio; he got his first experience recording in that little downstairs room.

I’d usually be the one who was singing. However, I loved R&B music so we invited members of the local, gospel church choir to come over and sing background to my vocals. That’s when he first realized that he liked recording. And that’s how it all began

When I signed with Morris Levy’s Roulette Records, I recorded a song with Brooks Arthur; Roy came along to the sessions; and, of course, he watched every little detail of what was going on; that’s when he started putting it all together.

I met Pam Sawyer at Roulette and we started writing together in New York. Roy and I’d go back home to our basement studio in New Haven and make a piano voice demo of our new songs; then we’d bring it back to New York where Pam would listen to it and she was always impressed by the quality of Roy’s sound. Roy was very creative, he’d add echo on the tape, he did what he could with the limited equipment that we had in those days.

One night Pam was at a party with her husband who introduced her to Phil Ramone and his partner Don Frey who both owned A&R Studios. And Pam said to Don, “You know, I’m writing with a girl named Lori Burton and she has a very talented husband who’s so interested in recording. You should really interview him.” So, Don interviewed Roy and hired him at A&R Studios. Roy was doing studio maintenance and eventually converted their 3 track to a 4 track studio.

In those days, A&R wasn’t doing late-night sessions. All the jingles they were doing were morning or afternoon dates. So, they told Roy, “You want to fool around on a board? If you want to be an engineer, you can practice late at night and get your own clients.” And of course, with me being a writer with Pam, we would meet all these groups and we’d bring them late at night to work with Roy at A&R. The studio was closed for work, the receptionist, everybody had left for the night. It was just Roy there booking the studio from 12 o’clock midnight up until 4 and 5 o’clock in the morning, and us bringing him the bands who were grateful for the free studio time. After working all night, Roy had to back come home, get himself cleaned up and showered, and then go back again in the morning to do maintenance.

It was around that time that Pam and I wrote the song, “Ain’t Gonna Eat My Heart Out.” We knew that Burt Berns had ties to the groups from England that we loved , so, we said to him, “We’ll give you six months with the publishing. We want either the Rolling Stones, the Kinks, Eric Burton and The Animals singing our song.”

Now, we’re waiting and waiting, and Berns finally tells us about this new group called The Rascals who were on Atlantic. He told us there was going to be a lot of promotion behind the group. And so, Pam and I agreed to meet with them and I played on the piano “Ain’t Gonna Eat My Heart Out.” They loved it and they loved “Baby Let’s Wait” too. So, we went to A&R and got Roy to record a demo. We only had one night to get the demo done and had to drop it off with Sid Berstein, the band’s manager at his home in NYC

So I went into A&R and made a piano voice demo. I was overdubbing the background vocals, I was playing a tambourine with my shoe, and I was singing lead. Roy was recording it all and he was great; that night we made an outrageous demo.

The group loved it, of course. That’s when Roy said, “Ask the band if they want to try and do some tracks over at A&R. I’ll be very happy to help them out.”

So, all of a sudden, we have The Rascals coming into A&R Studios which at that time was on 48th Street. They came in after hours and were doing everything that they wanted to do. Before you know it, they were laying down tracks for “Good Lovin’” and “How Can I Be Sure.” Roy recorded everything on that first album. He gave all the tapes to Tommy Dowd and Arif Martin at Atlantic and, as far as the band was concerned, they loved what they did with Roy.

Then, when the record finally came out, Tommy Dowd, Atlantic Records engineer, got all the engineering credits. Roy told me, “Lori, those tracks sound like mine. I know what I’ve done. I know my stuff.”

Roy was right up on top at A&R by then anyway. I mean, he’s now doing well-known artists . He had his own crew. Roy is the one who originally hired Shelley Yakus over at A&R. I remember Phil Ramone’s saying that he didn’t see Shelly becoming an engineer. To which Roy replied, “No, I see something in him, I want him, I’ll train him.” And he did. Roy trained all these people that Phil would have rejected. Shelly, Jack Douglas, Jimmy Iovine, Jay Messina, all of them. Roy saw something in all those kids who would eventually become great engineers and producers. I don’t know what it was, but he had that intuitive feeling about young talent. He just saw it. He put them all through such hell. But he knew talent when he saw it.

Roy was keeping all kinds of insane hours in those days. Groups were coming in at 12 o’clock at night and working until 3 in the morning. He and Shelley were recording every night, sometimes standing up in front of the console asleep. That’s when Roy started in with the fire extinguishers. It became a riot. He’d blast the engineers with fire extinguishers to shake things up and wake them up. And he especially loved to do it to Shelley, because Shelly would look as if he was grooving to the beat, standing there at the board with his eyes shut. It became a Record Plant tradition using fire extinguishers on the assistants engineers.

Then around 1970 along came a band from Michigan called the Arbors. They were managed by Art Ward, one of the owners of A & R Studios. Art asked Roy if he would be interested in recording them and to ask me if I had any songs for them. Pam and I weren’t writing together anymore. I was free as a singer.

At that time I had an idea for the song, “The Letter,” which was already a hit by the group “The Boxtops;” I wanted to do a version of it like Jose Feleciano’s version of “Light My Fire.”

Now, Phil Ramone, one of the owner at A & R had originally recorded the Arbors. And now Art Ward wanted me, our arranger and Roy in his private plane to see The Arbors perform in Atlanta Georgia, and this wasn’t going down very well with Phil.

To make matters worse, Phil suggested that he wanted to record and produce me. Roy was my engineer and he and I produced me. That’s when there seemed to be a distance created between Roy and Phil.

So, Roy goes into A&R one day, and there’s a notice up on the bulletin board: “Roy will be leaving us, and we all want to wish Roy well …” It was a horrible way to be let go. But Roy never confronted Phil about this. Roy knew that he had become a threat. Roy said, “Lori it’s all right. This was coming sooner or later.” Roy just got his stuff and left.

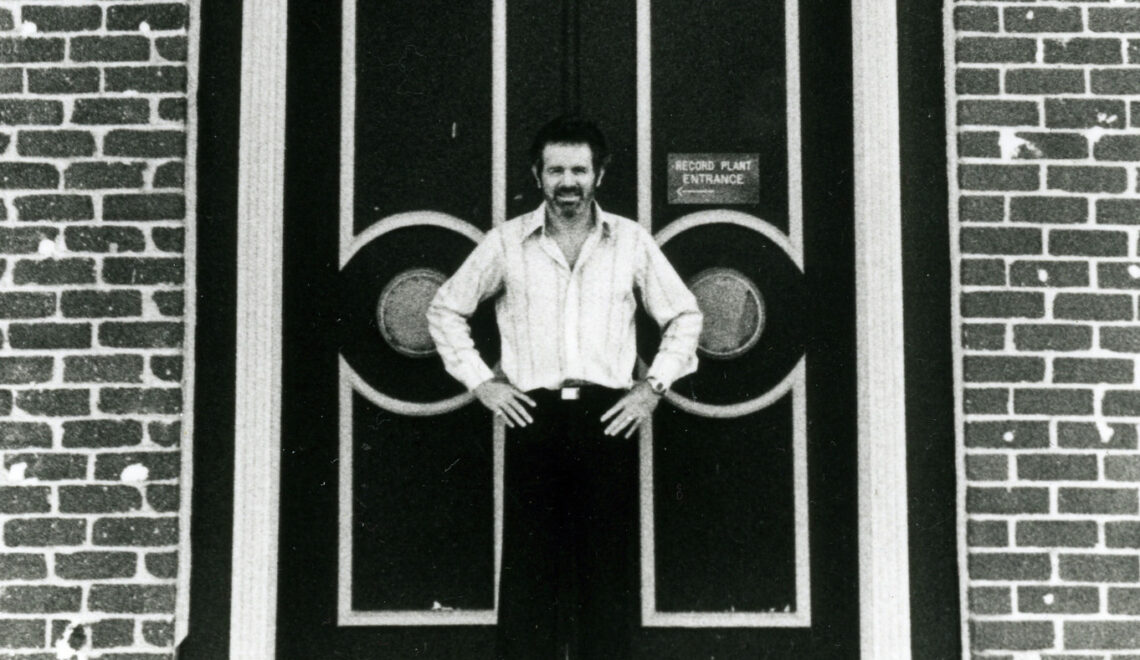

By the time Roy left A & R, everyone in town knew who Roy Cicala was. By then Chris Stone and his partner Gary Kellgren had sold the New York Record Plant to a company that became Warner Communications and Chris was spending most of his time in LA. Gary was building the new studio and Chris needed someone to run New York. So, Chris offered Roy a deal and told him early on: “Look, you know, Warner is looking to unload Record Plant.” Roy told me that one night, and so, I said, “Roy, well then, why don’t we buy it?” At first, he thought I was crazy. So did our attorney. But Roy always liked a challenge, so he got back to Stone and told him, “Yeah, I want to buy it. I’ll buy Record Plant New York.”

Roy put together a group of investors. A former Warner exec named Abe Silverstein was one of the first backers; he was looking for something to do and he liked all the crazy people that would come into the studio, so he’d want to hang out. Abe was good for Roy. He kept Roy’s feet on the ground.

Then Roy met John (Lennon). John liked him because he knew Roy would always be straight with him. Roy once told me, “You know, Lori, I’m the only one who’s honest with the guy. He asks me something, I’ll tell him. I’m not going to go ‘yes’ to him.” Roy handpicked the others who got to work with John. Jack (Douglas) and Jimmy (Iovine) were there with John all because of Roy.

There’s that famous story about Jimmy Iovine. It’s a Sunday or something, some people say it was Easter Sunday but I’m not sure, and Roy called Jimmy up, he didn’t care what time it was or that Jimmy was with his family. “You want to be an engineer?” If Roy Cicala called you up 3 in the morning, you better get dressed and come to the studio. There’s an artist here, and you’d better be ready to work. “You don’t want to come in?” Then you don’t really want to be a Record Plant engineer.

Roy got Jimmy Iovine to come in on Sunday, all the way in from Brooklyn. Jimmy walked into the studio and saw John Lennon there waiting for him to record and Jimmy almost has a heart attack. Roy and John just laughed at the look on the kid’s face. The assistants, they never knew what was coming down with Roy; they never knew what to expect.

There was always a line of young kids ready to work at Record Plant, wash the floors, run errands. We called them Generals because they did “general” things. The smart kids would come in and just say, “I just want to work. I’ll do anything. I don’t care. I want to be an engineer.” And anybody who could get in the door, Roy would interview. I’m sure there were people that came in that he didn’t choose, but those that he did eventually hire were usually people out of left field. Roy had faith that they would work out. Shelly became a very good engineer. Jimmy (Iovine) knew he wasn’t an engineer and became a great producer. Jack Douglas caught on right away. When he was around Roy, he was all ears. There was something that Roy — I guess almost by intuition — saw in all those people.

Roy and I, at that point, were having personal problems. We were living in Montclair, New Jersey but Roy was always in the studio. I found out that Roy had a couple of “indiscretions” but at least at that time we somehow worked things out. And next thing you know, I was pregnant with my daughter Shaun — just when John first told Roy that he was going out to California and that he wanted him to go out there with him to record.

Roy went out to California for a short while and came back only when the baby is born. He was here for six weeks, with John calling for him all the time to come back out to LA.

That’s when Roy got this idea that he wanted me to go out there with him and the kids. He told me he would bring his mother, Molly, to babysit. Roy said, “You know what, Lori? We’ll bring her out. It’ll be good. She can keep an eye on Jade and Shaun.” Shaun was just a baby; only six weeks old. Jade was three-years old and he was quite a handful. Roy’s mother, Molly, was not going to be able to handle this alone and would need someone to help her. Anyway I agreed to go.

It became this crazy thing. We were all living in this tight, little bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel together. It was beautiful, but it was just a bungalow. We had a little living room, a little kitchenette, and just two bedrooms. It wasn’t like the house that we were living in in Montclair, three floors with 14 rooms, where Jade could run around without getting into Roy’s hair.

Roy’s mother didn’t know how to handle the situation. I had to hire a nanny to take care of Jade and Shaun and his mother Molly. Jade was playing tricks on his grandmother that she couldn’t handle, and she’d be going, “Roy! Roy!” and Roy was saying, “Ma, I don’t want to hear it. I got to go and do a session.” Roy would come in exhausted after working late hours in the studio; he’d come in at 5:30, 6 in the morning, wanting to do nothing but go to sleep. And there was Jade jumping on our bed. “Dad, wake up!” So, Roy was flipping out.

It was total insanity in the studio too. Remember, at that time John and Yoko had broken up. John would drink and when he drank too much he became Jekyll and Hyde and was totally out of control. May (Pang) was with him alone in LA, and John was in a free-for-all. He could do anything he wanted. You had no idea of the insanity that was going on at that time, and John was drinking more and more and out of control. And there Roy and I were in this tiny bungalow with a baby and a toddler and my mother-in-law.

Roy would come home and tell me things about Phil (Spector) shooting guns off in the studio. About this jam session with Ringo and Mick Jagger. Cher coming in wearing a see-through outfit. Elton John was there collaborating with John. And then Phil Spector kidnapped John and brought him up to his home, his mansion, and tied him up so he couldn’t get away. All the time May’s calling Roy up at the studio to help, and Roy’s calling me up in the bungalow, like, “Lori, you don’t know what’s going on here. It’s insane. Phil tied up John. . Nobody can find John. Yoko’s calling all over the place. May is distraught.”

That’s around the time I went back home with the kids. I had had enough. And Roy and Jimmy (Iovine) came back not too soon after; they had their record in the can. All the while, Yoko was calling Roy up in the studio and complaining, “How am I going to get John back?” Roy ended up telling Yoko to call me up at home in Montclair; he told her, “You know, Lori’s into spiritual things. You should talk to Lori. Give her a call. She’s all into that. She could tell you if John will come back to you.”

That’s when I got a call from Yoko. There I was taking care of my kids during the day, wondering who was going to wake up in the middle of the night. And I have Yoko on the phone with me, saying, “Roy told me that you have a psychic ability. Do you have any feeling tonight about John?”

How did I know what he was doing? All I said to her was, “You know, I’m sure he loves you.”

And I called Roy back at the studio and said to him, “Yoko keeps calling me. I can’t deal with it.” He said, ” What am I supposed to do? I’m in the middle of a session. She’s calling me up and crying, so I got her to call you. Please, Lori, I need a break from her.”

Everybody wanted a piece of Roy’s time. I’d always get a call, “Where’s Roy?” Sometimes I’d go into New York to shop and I’d be there in the reception area, maybe at the desk, waiting for him to finish up for the night. He’d come in, saying, “Hurry up. Let’s go now.” I’d go, “What?” “Hurry up. Just let’s go I don’t want to be in here. I’m never going to get out tonight.” As soon as the clients saw him, they’d be asking for help, “Oh, Roy, wait, wait. Before you go.” Oh no. He knew. Here it goes.

He was always in demand in the studio. But he couldn’t do every session by himself. Chris Stone originally taught him how it worked. He’d say to a client, “Look, I’d love to work with you, but I’m in the middle of another album or something I’m doing,” and he’d add, “so, I’m going to give you somebody who will be great.” If Roy said so, it was all right. Whoever Roy was going to assign to the date, they knew that it would work out. … and then, later, when Roy would pop his head into the session, yeah, it was a really, big deal. He would give some input to the engineer or the producer and then leave. They’d go, “I don’t believe it. he just said this and it was great.” He appeared, made it better, and then left.

Roy was originally offered Bruce Springsteen. He wanted the business for the studio but didn’t want to do the sessions himself. Frankly, at that point he didn’t want anything. He was just finishing up with Lennon. He was tired of all these crazy hours. You know, they’d tie the engineer up, the producer up, the studio up. You’d live and breathe those groups for days and weeks at a time, and I think, after Lennon, he started to back off, even with Lennon! He heard that Bruce Springsteen was a perfectionist in the studio, that he would be up all kind of hours and days or whatever, and Roy didn’t want to deal with it. There was a lot of money behind Bruce at that time, a lot of promotion. He was on the cover of Time magazine, but Roy didn’t care.

Roy knew that Jimmy (Iovine) was ready as much as he was ever going to be . Jimmy loved music. He loved all the stars and who was at this club and that. So, Roy knew that Jimmy was very excited. “Oh, Bruce Springsteen! Wow!” He said, “Really?” He said, “You know what, Jimmy? I’m going to give him to you.” “You’re kidding me.” “No.” He said, “Really.” He didn’t want it. Roy refused it, he gave Bruce to Jimmy.

Roy’s perfectionism was the root of the problem. He couldn’t do a project if he couldn’t do it right. Everything always had to be perfect, and everyone knew what Roy expected. If a piece of equipment wasn’t working right, he’d suddenly go crashing through a room and go up to the engineer and scream, “What’s the matter with you? This was supposed to be fixed two days ago, all right? That’s what I need.” And they’d all shake. The engineers knew that when Roy got upset it meant trouble.

Roy was so involved with the equipment and sound that he wasn’t paying attention to the front office. When he hired Eddie Jason, Eddie Germano, as studio manager, it was the beginning of the end. From the start when he was first hired, Eddie was planning to compete with Roy; he wanted his own studio, he needed someplace to meet clients and learn. In1975, after Roy introduced Eddie to John Lennon, Bruce Springsteen and so many others, he just looked at Roy one morning and said, “I’m leaving.” And Roy asked, “Where are you going to go?” Eddie replied, “Oh, I’m buying the Hit Factory.” Roy had been spending a real lot of time with John Lennon, working all hours of the night. But he wasn’t paying attention to what Eddie Germano had doing behind the scenes. Eddie used Record Plant as a launching pad for his buy-out of the Hit Factory. And it really got bad – especially when he started stealing Record Plant engineers. So now Roy was in competition with Hit Factory, and he was really upset about how Eddie had used him, but there was not much he could do.

It was around that time, 1976, that Roy and I separated; and it took a personal toll on both of us. Abe Silverstein told Roy to take some time off and suggested that he go to Brazil. So, Roy took a trip to Brazil and it was his therapy, you could call it. He started losing interest in the studio. Everything was Brazil in those days. I remember there was a time when we were thinking about getting back together and he started taking me out to Brazilian restaurants, Brazilian clubs, having Brazilian drinks. And I remember saying to myself, “What am I doing? I don’t know what’s going on with this Brazilian thing? I don’t know this man anymore.”

Something was off. Roy started going back and forth to Brazil, and he’d be away for months at a time and nobody was watching the store. Not surprisingly, the Record Plant started looking really shabby around that time. Nothing was going back into the studio. Roy was in another world. The studio was losing a tremendous amount of money; and the more it lost, the more Roy lost interest. There was nothing left for him to do. He was disgusted, and Roy just wanted to go on to something else.

Once Roy started leaving the country it became a crazy house over at Record Plant. Everybody was doing what they wanted to do. Cash deals were being made. We had to pay back taxes and pay the rent or else we were going to be shut down. Even with two bookkeepers we were behind on all the bills. I had to do collections. Everyone was taking advantage because Roy wasn’t there.

This went on for quite a while, and, finally, the studio went into Chapter 11. I knew it was bad and called Roy and said, “Let me come into the studio and see what I can do to help.” I hadn’t been in the studio for years. I wasn’t working there, and we were divorced, of course. I was in another relationship with a man who would become my second husband. But I still cared about Roy and Record Plant. So, he hired me as the new studio manager.

I walked in, and I saw what was going on. I said, “Roy, I’m going to shake up everybody in there.” He said, “Go ahead. I don’t care what you do.” I said, “Well, there’s going to be people that are going to be …” He cut me off, “I really don’t really care. Do what you need to do. I trust you.”

Jack Douglas had a studio booked with Aerosmith, and a few days before they were supposed to start a month’s worth of work, they cancelled out. So, I billed them for it anyway, and the studio manager who was on his way out said, “You can’t do that to Jack … That’s Aero …” I said, “I don’t care who it is, They booked a studio, okay? With two-day’s notice? They can’t cancel out a month? What are you, out of your mind?” How are we supposed to fill up that room?” I didn’t care. And Columbia paid it. They didn’t care. Nobody cared but I did and I did everything that I could do to keep the business going; I knew how Roy ran the studio when we were together, and I was running it the way he would have run it himself if he were there.

Gene Simmons and KISS always recorded at Record Plant, but towards the end they came in and saw how shattered it looked. The lounge area was dilapidated. Cotton was coming out of the cushions. All our long-time customers were going somewhere else — Power Station, The Hit Factory, Electric Lady. I heard that Paul Stanley was shopping for studio time for a new group he was working with, and like a lot of our clients, Eddie Germano was also trying to get him over to the Hit Factory.

So, I called him up and said, “Paul, I’m going to just be honest with you. I’m now a studio manager. Roy’s not here right now, and I’m trying to get the studio back in shape. What can I do to bring KISS in?”

He said, “Well, really, actually, nothing.”

So, I asked, “What group are you working with, how would you like to have Ahmet Ertegun hear them?

He said, “Really?”

I said, “I’ll tell you what. If I get Ahmet Ertegun to come and listen to them, will you come and do the dates at Record Plant?”

He said, “You got a deal.”

So, I called up Ahmet who I knew for years and I didn’t tell him anything about Paul Stanley’s new band; instead, I told him that KISS was looking for a new record deal and that Paul Stanley was working in town at a nearby rehearsal studio. So, Ahmet goes to the studio and listens to the new band but he’s there really to talk Paul into signing KISS to Atlantic.

KISS never went to Atlantic but I got Paul to work at Record Plant.

We were trying to keep up with the taxes, rent, payroll but couldn’t. I felt horrible. Nobody could save the studio at that point. The studio finally went into Chapter 7. I guess, when you come right down to it, my trying to save the Record Plant towards the end was my way of trying to save Roy.

Roy left to Brazil for good. He eventually became very ill, but he didn’t want to face the fact. All the bitterness from the divorce and the loss of the studio were over. Our egos weren’t there anymore. We still loved and respected each other very much. But he was in Brazil and terminally ill. I wanted Roy to come back to the states where he could be near our children, Jade and Shaun, but he wasn’t ready to leave Brazil yet; he was waiting for his daughter from another marriage to have her baby. He did say that he didn’t want to die in Brazil and wouldn’t, and for me not to think about such things. Unfortunately, he passed away two weeks before the baby was born.