Birth of a Record: The Witnesses

By Mr. Bonzai

Bill Szymczyk and Joe Walsh: “Hotel California”

Recorded at the Record Plant in Los Angeles and at Criteria Studios in Miami. Released in 1976, two Grammy awards, over 32 million copies sold worldwide.

Producer Bill Szymczyk, Mr. Bonzai and singer-songwriter Joe Walsh speak on stage during the 2016 NAMM Show at the Anaheim Convention Center on January 23, 2016 in Anaheim, California. (Photo by Jesse Grant/Getty Images for NAMM)

Hotel California is the fifth studio album by the Eagles, released in late 1976. Produced by Bill Szymczyk, it was their first album with guitarist Joe Walsh. The album became the band’s best-selling studio album, with over 16 million copies sold in the U.S. alone and over 32 million copies sold worldwide. It topped the charts and won two Grammy Awards for “Hotel California” and “New Kid in Town.”

“Hotel California” further established the group as the most successful American band of the decade. The song “Hotel California” is considered by many to be one of the greatest rock songs of all time; it was ranked number 49 on Rolling Stone ’s list of “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time”. The guitar duet at the end of the song was performed by Don Felder and Joe Walsh. The album also features “Wasted Time”, “Victim of Love”, and “The Last Resort”.

Original vinyl record pressings of “Hotel California” (Elektra/Asylum catalog no. 7E-1084) had custom picture labels of a blue Hotel California logo with a yellow background. There is also handwritten text engraved in the run-out grooves of each side, continuing an insider joke the band had started with their previous album “One of These Nights”:

Side one: “Is It 6 O’clock Yet?”

Side two: “V.O.L. Is Five-Piece Live”, indicating that the song “Victim of Love” was recorded live, with no overdubbing.

Joe Walsh, songwriter, composer, multi-instrumentalist, and record producer, has been a member of five successful rock bands: the Eagles, James Gang, Barnstorm, The Party Boys, and Ringo Starr & His All-Starr Band. As a member of the Eagles, Walsh was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998, and into the Vocal Group Hall of Fame in 2001. The Eagles are considered to be one of the most influential bands of all time, and they remain the best-selling American band in the history of popular music.

Bill Szymczyk, music producer and recording engineer, is best known for his work with rock and blues musicians, most notably the Eagles. Unlike many producers, Szymczyk has no background as a musician. He was originally a sonar operator for the U.S. Navy and took audio production classes as part of his Navy training. Besides his work with the Eagles, he has produced hit songs and albums for such diverse artists as B.B. King, Joe Walsh, The James Gang, and Elvin Bishop.

As a young record producer looking for talent, Szymczyk remembers his first meeting with Joe Walsh, “I went out to Cleveland, because an ex-roommate of mine was working in a bar called Otto’s Grotto and there were a lot of bands going through there. He said, ‘You ought to come out here. There’s a bunch of great bands.’ I went out and I looked at the bands he was talking about and I didn’t like any of them.

“There was another guy named Mark Barger who said, ‘I’ve got a band for you, come and see them.’ We walk into this club. The band was playing around a corner from the entrance and we couldn’t see the stage, but we could hear them and I thought, ‘That sounds like a 5-piece band.’ We come around inside to actually see the band and it’s 3-piece and it’s Joe playing the most ungodly, wonderful guitar — it sounded like at least 2 or 3 people. I was intrigued immediately. We hung out that night after their set and talked a little bit and I said, ‘I’d like to record you guys,’ and they said, ‘Okay.’”

Joe Walsh remembers, “We played at Packard Music Hall in Warren, Ohio. Warren’s south of Cleveland and Bill drove down and I met him. We went outside and I remember sitting on the lawn. I liked Bill because he had really cool boots on. He says, ‘I would like to approach you about recording. What do you think?’ I said, ‘Well …’ I thought about it. We went and talked band-wise and I finally came back and I said, ‘Okay, but you see, you’re going to have to stay up for a couple of days in a row and so let’s find out if you can do that first,’ and he did.”

Szymczyk entered into his era with the Eagles during the recording of “On the Border,” which was already in progress by one of his heroes, producer/engineer Glyn Johns.

“My concept of recording the Eagles,” says Szymczyk, “was to combine the American R&B sensibilities of Tom Dowd at Atlantic Records with the bombast of English rock and roll by engineers like Glyn. I thought if I could bring those two elements together, it would be pretty interesting. I knew Glyn well and when the Eagles asked me to produce them, I said I would, but only if I could call Glyn Johns first. I called Glyn the next day and said, “Glyn, the Eagles want me to produce them.’ He said, ‘Better you than me, mate.” I said, ‘Is that a yes?’ Although they had recorded a number of tracks with Glyn, only two were kept for the final album.”

He recalls his first meeting with the band. “I was working at Record Plant studios in LA, doing something. I forget what session it was and Joe Walsh was the one that said, ‘You’ve got to really talk to these guys.’ I replied, ‘I don’t want to do a country band. I want to do a rock band.” Joe replied, ‘No, they want to rock, really. They want to rock.’ I said, “Okay, we’ll talk.’ It was Joe and the band and myself and their manager Irving Azoff.

“We met at Chuck’s Steakhouse which was the meeting place just down the street from the Record Plant. If you went out the back door of the studio into the alley, you could walk down to the back door of Chuck’s and inside there was a big table there. We called that the Record Plant Table. It was private and you could have meetings and do some business there. We had a meeting and they grilled me and I grilled them. The next day they called and said, ‘You’ve got the job.’ I said, ‘Great, let’s go.’

“’On the Border’ went quickly. The songs were already written and I think it was a matter of 3, 4 weeks tops at Record Plant LA, Studio A, and we were done. That was the last time that happened and it got progressively worse. Anyway, I was going to England for some reason and I called Glyn and said, ‘Hey, I’m over here. I got the new Eagles record. Would you like to hear it?’ He goes, ‘Okay, come on over for dinner.’ I went over for dinner and we had copious amounts of wine and after dinner, he puts the record on and after it’s over, I said, ‘What do you think?’ He says, ‘I’m not real fond of it.’ I said, ‘What do you think about the two mixes that I did of your songs?’ He goes, ‘I hate it. Let’s have another glass.’”

Szymczyk recalls the recording of the following album, “One of These Nights.” “On purpose, we set out to rock even harder. It got a little further away from the country and a little more toward the rock. Bernie Leadon was the consummate country musician in the band and the more we rocked, the less he was into it. We had finished some tracking the night before and the next day around 2 in the afternoon we all get to the studio and we’re listening to different takes from this tune that was a real rocker from the night before.

“We listen to 4 or 5 takes and I’m behind the board and all the band’s behind the board with me, except Bernie. He’s on the couch in front and I can’t see where he is. He’s sitting in front of the console. I asked everybody, ‘What do you think?’ One said I like Take 2. Another said I like Take 3. There was nothing from Bernie and I said, ‘Bernie, what do you think?’ There’s a long pause. Then he gets up and he stretches and he goes, ‘I think I’m going surfing,’ and he left. That was when we knew Bernie wasn’t long for the band and shortly after the album came out, that was the end of Bernie’s tenure with the Eagles.”

Joe Walsh adds, “Bernie was really a purist for country music. He wanted to sit in a rocking chair on the front porch and play acoustic guitar. He just did not feel comfortable going in the direction that Don and Glenn wanted to go. They were afraid they would paint themselves into a corner as a country rock band and they were one of the pioneers in that genre. Glenn thought if they could mix what they were doing with a portion of rock and roll, that would be the answer.

“Another thing was that the Eagles had trouble towards the end of their performance set. They needed a closer when they played live and they didn’t have any rock and roll songs. They approached me, and Bernie agreed to stay for a while and finish the tour and of course, everybody said, ‘Well, this will never work,’ but in the Southern California community at the time, we were all hanging out. My band played shows with the Eagles and I was not in the band, but we were pretty much on the same wavelength and we decided that we would try it.

“We didn’t really know if it was going to work, but we decided to try it. I just thought, with those singers, what great, great music to play some kick ass big guitar behind it. I wanted to be part of it. I had a great solo album, a solid solo career, but a lot of things come along with that that are non-musical. You’re not aware of it until they show up. That is the hiring and the firing and all of that, making all the decisions — and writing by yourself.

“I was starting to feel stagnant and it just didn’t’ feel right, so I wanted to be part of something. I wanted to be back in a group. There we were and that’s where everything was — that’s the proper perspective to begin talking about ‘Hotel California’.”

Sessions for the album began in April of 1976. “They call me up,” says Szymczyk, “and they say, ‘Okay, we’re ready to record, book some time. We’re going to have a week or two of rehearsals before we go in and see what we’ve got.” I get to LA and they had rented Ricky Nelson’s house up in the hills somewhere and had put all the gear in there and that’s where they were writing, rehearsing and so on and so forth. I show up, we get together and I said, ‘Okay, let me hear some tunes.’”

“They played me one song, ‘Try And Love Again.’ It was Randy Meisner’s song and I said, ‘Fantastic. It’s a great song. Good start, what else you got?’ Nothing. ‘Oh, we got some licks and we got a couple of verses and we got a little bit of this.’ Walsh adds, “I said, ‘Don’t worry about that, Bill.’” Szymczyk continues, “We got two weeks in the studio next week. ‘Don’t worry about that, Bill.’ Eventually, things came to fruition, but this was really the serious beginning of writing in the studio.”

Walsh remembers, “Prior to that, we went to Australia and I had to learn all of Bernie’s parts. I had no idea what a great guitar player he was at coming up with off the wall original parts, until I had to learn them. Holy shit, this guy’s good. Anyway. I had to learn all that and when we took it to Australia, because it was January and it was summer there, we knew at that point after playing a dozen live shows that it was going to work.

“We really didn’t know how to start. We just knew that it was going to work. We had no concept and the only way to do it is just to start. You’ve got to start somewhere and so we did. We brought ideas in. What we did was everybody had some pretty cool stuff, parts of songs, and I had a lot of great guitar licks and Don had some words and, of course, Glenn being from Detroit, he knew where he wanted to go.

“We took all of that and put it on a table like this and said, ‘Okay, let’s pretend this is a jigsaw puzzle.’ Well, this here, these two things go good here. This isn’t part of that. This is going to have to be another song,’ and we started that way. Then we presented that to Bill and little by little things started to take shape.

“Don and Glenn, brilliant song writing team, everybody knows that and that’s when they worked the best. When you brought something in and they would sort through it and pick the stuff that got them off and then they would run with it. Then they’d go to Don’s house or to Glenn’s house — actually, wherever they lived. We all lived in the same car for about 6 weeks.

“Don and Glenn would get a framework. Glenn was great at that. They would get a framework of the song, a rough idea of how we’re going to start, what the verses are, what the choruses are, and of course Don would take that and start writing words. Don Felder, Randy and I would play Ping-Pong.

“Then they would come back and Bill would sit in the control room and oversee it and arrange it and tell us what was going to work and what wasn’t. We all had ideas and stuff, but Don and Glenn were great at crafting songs. They just needed material to work with and that was our job. That’s gradually how it took shape. Once we got going, we started to see progress and then rather than be clueless, like in the beginning, we were on our way. The toughest thing is to get started.”

Once the foundation was laid, the album started to get off the ground. “Lift-off,” says Szymczyk. “I’ll tell you how this worked. We’ll take just an example of the song itself, ‘Hotel California’. We recorded that track three different times, because of this reason, going on what Joe said. Don Felder came in with a 12-string descending guitar line that everybody dug and it was like the intro to ‘Hotel California’. We all dug that and we agreed, ‘We kind of got an arrangement and we had no clue what the words were going to be or anything. We did a track at the Record Plant.

“Don and Glenn take it away, take the rough mix away and now they get a start to form what’s this is going to be about. The first time, they came back and said they had a melody but Don said it was in the wrong key. We cut it again in the right key but it still wasn’t formed into a real honest to god song yet. They go, ‘Right key, too fast, we’ve got to cut it again.’ We did cut it again and that’s the one that everyone is familiar with.”

Walsh explains, “Yes, and Don knew. He didn’t have the words yet but he knew where they were going to be. He knew where they were going enough to tell us the structure of a verse and chorus. I did not know what to do with these guys, because we had a great take, but he couldn’t sing the low notes. It was too high.”

As with many recording groups, Eagles’ songs-in-progress had temporary titles. “We had stupid titles for all the songs,” says Walsh, ‘Hotel California’ was called ‘Country Reggae’. Until we got some words written. And when Don Felder took a look at the guitar track, we decided that that should all come later. We would cut a track of the background rhythm parts, so that there was something there and because we needed Don to sing it first to make sure that we didn’t play over him when he was singing. He had to sing it first so we knew how to orchestrate the guitars.”

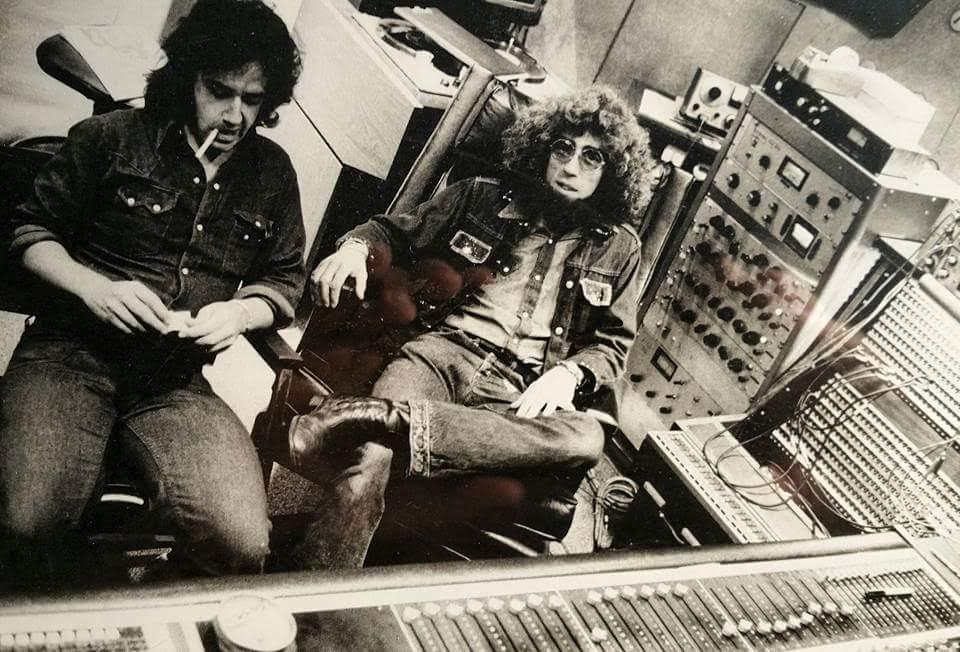

Szymczyk adds, “I’ve got to say something about the guitars on this song. This was probably one of the very, very highest points in my life — sitting in the studio with Walsh on one side, Felder on the other and the vocal’s done. Now we’ve got a vocal, we have no lead guitar parts. It took us two days, two full days of just the three of us, trial and error, ‘If I do this, you can do this, and the harmony will be here and then I’ll do that and then you do this, and back and forth, trial and error.

“Trial and error, punch, punch, punch, 8 million times until the end of that two days is that unbelievable guitar stuff at the end. Actually, all the way through, but mostly at the very end of ‘Hotel California’. That’s by far, one of the highest points of my career.”

Meanwhile, the other Eagles were playing Ping-Pong and taking it easy. “Yeah, whoever was on duty got the control room,” says Walsh. “We stayed away when Don was singing, of course. He would do that with Bill and Glenn would pop in every once in a while. When it was time for Don Felder and I, we wanted to put a layer of things on. Kind of like a mariachi band’s trumpets. That was the first thing we wanted to do and we wanted to play those together. We wanted to play with each other a whole part.

“Then he got the first verse and I got the second verse and then we figured, at the end, we would go at it and the last thing we did was really go at it. Don Felder and I were always very competitive, but it was good. We really respected each other and we pushed each other. We pushed each other on stage and when we were playing together. It was really competitive and really serious but it was really good for creative energy. Controlled tension fuels creative energy.

“Did we fight? Yeah, we fought. In any relationship, you fight. Any meaningful relationship, a marriage, yeah, you fight, you disagree. I always said that it was a democratic dictatorship. We got to vote but Don and Glenn decided.”

The song “Hotel California” has been compared with the recording environment at the LA Record Plant. It had themed hotel-like bedrooms. There was the “Rack Room” with ropes and winches. There was the “Sissy Room” with lots of frilly bedspreads and drapes. There was the “Boat Room”, with porthole windows and a spiral staircase leading to a loft bedroom above. There were mirrors on the ceilings and there was a labyrinth of dark hallways and corridors. Does the studio layout figure into the lyrics and the meaning of ‘Hotel California’?

Walsh says, “The song has been so totally over analyzed.”

As for other songs on the album, “Life In The Fast Lane” is one of Szymczyk’s favorites, and it had strong contributions by Joe Walsh. Szymczyk elaborates, “The thing that got put in the jigsaw puzzle was doo-lil-loo-loo-diddle-doo-doo-doo and we went, ‘Okay, that’s a good start. Let’s go.’”

“That was a coordination exercise,” Walsh explains. “I would do it in the dressing room before we played live. The pa-ra-ra-ra-da-ra-da-da is cross picking and such. Don and Glenn heard me, came in and said, ‘What the hell is that?’ and I said, ‘I was just warming up with some lick I had. It’s just my warm up exercise.’ They said, ‘No, it isn’t.’ They put it in the jigsaw puzzle and Don Henley wanted to write about was Los Angeles at the time, which was life in the fast lane, and so same thing, Glenn orchestrated it. We knew it was going to be the most rock and roll thing that the Eagles had attempted so far. You close the show with that — you’re going to get an encore, and so they turned me loose on that one. And Don did a brilliant job of telling a story with the vocals and Glenn arranged it. Then we got Bill to do the Hendrix flange, the full on flange at the end.” Szymczyk affirms, “Record Plant co-founder Gary Kellgren taught me how to do that.”

The backstory on “New Kid In Town” further deepens an understanding of the creation of the album. “Bob Segar had connections to the Eagles family,” Walsh explains. “Glenn had been in Bob Seger’s band in Detroit. I mean Bob was an honorary Eagle. Glenn was also in a band with a guy named John David Souther, who wrote some songs for Linda Ronstadt. He’s a great songwriter and so if we had a party or something, all these people would be there. Jackson Browne, of course, wrote ‘Take it Easy’ with Glenn, but they brought Bob out and at the time, Hall and Oates had just put out ‘Sara Smile’. Daryl Hall was the ‘new kid’, because that song just went, Boom — #1, and just parked there on the charts. Everybody said, ‘Who are these guys?’ and we noticed that. When there’s a new kid in town, everybody pays attention, until there’s another one and so that’s how that song came around.”

“Vinyl Graffiti” is Szymczyk’s term from the mastering of vinyl records, referring to the stylus used in the process to allow the operator to write notes on the master that are duplicated on each album pressed.

“I learned that from Phil Spector,” says Szymczyk. “When ‘You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling’ came out, I was in love with that record and that was obviously very, very early in my career. I was cutting dubs then and I remember getting the record and saying, ‘How in the world did he get 7 minutes on a single 45rpm record? It had to be mashed together.” I started looking at it through the microscope on the lathe and I come to the close out of the groove and there it was, ‘Phil and Annette.’ I discovered that you could write message there. That was it for me.”

“That’s called a scribe,” explains Walsh. “It’s usually a record company ID number when they mastered or a pressing plant batch number in case they made a bad batch. I think Bill started doing that when we were mastering records for The James Gang. He started writing secret messages just outside of the label where the groove is in the middle, where it goes around and around.”

“Every time it would have something specifically to do with that album,” Szymczyk recalls. “Maybe a phrase that had come up during the course of that album or something along those lines, so it would be album specific for whatever we would put in there. I would never tell anybody what I was going to put in there, until I mastered it. People would get the staff pressing and go, ‘Oh, okay,’ or ‘What?’ For ‘Hotel California’, I wrote ‘Is it 6 yet?’ because we didn’t drink in the studio until 6pm. I made a rule after it got a little unruly at first and whenever it gets unruly, you need rules. I said, ‘All right, guys, we have to get in here at 2 o’clock in the afternoon and we’ve got to get work done until 6, so I don’t want no ingestion of anything other than coffee. 6 o’clock you can get your beer, get your whatever.’ You know what I mean.

“In between takes they’re all out in the studio and I’m maybe changing reels or something like that in the control room and you hear them muttering. It would be like 4:30 and you hear somebody muttering, ‘Is it 6 yet?’ That’s the story of why I wrote that on the first pressing of the album.”

Recording engineer and producer Gary Kellgren co-founded Record Plant with his business partner Chris Stone in 1968. “Chris was really great,” says Walsh. “I could not get him and I tried. We would come up with these ridiculous ideas of stuff we wanted to try or stuff we wanted to do and he would say, ‘No problem. No problem, I’ll get the tech guys on it.’” I’d call him up and say, ‘Chris, I’m in jail. What do I do?’ He’d just say, ‘No problem, no problem. Sit tight.’ I really tried to freak him out a couple of times but I could never do it.

“Let me just say that it was a kind of a painful birth, ‘Hotel California’. Not too bad, not too bad once we got going, but the funny thing is that everybody thinks we knew what we were doing. That didn’t really matter. We just knew it was going to work. We weren’t famous yet. I mean we weren’t like we are, like it turned into, but I think one of the greatest rewards for all of us is to have been part of something that affected that many people on the planet, beyond our wildest imaginations. And it’s good to feel like we made a valid, profound statement for the generation that we represented.”