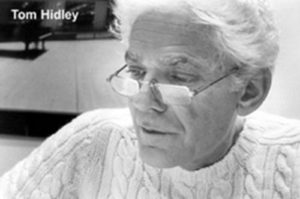

A 2015 conversation between audio trailblazer Tom Hidley and Record Plant co-founder Chris Stone (moderated by Steve Harvey).

Tom Hidley: You can’t really talk about Record Plant unless you talk about two main individuals. The first being Gary Kellgren, who was the visionary behind the package, and Chris Stone, who actually made it happen financially, following budgets and allocations, deciding what got built and what got developed, and what was put on the R&D table and how it was going to get funded, and so on. All through the history of the company, at least while I was with it, Gary and Chris jointly made this thing work.

Chris Stone: You made it work, too, Tom, because you were the guy who built all the things that Kellgren could only talk about.

Tom Hidley: Well, Gary was a visionary. He told me a couple of things in the beginning even before the design began. He said, “Tom, I want a a studio that looks and feels like a home living room, not the sterile hospital look and feel.” Remember, back in those days, studios by and large around the world were asphalt tile on the floor, acoustic tile on the ceiling, some basic wall treatment on the sides, and alternate layers of some other devices of ages gone by. Oh, and a big plaque clock on the wall.

Chris Stone: And fluorescent lights.

Tom Hidley: Yeah, and fluorescent lights. All that stuff was the earmark of studios dating back to the 30s, 40s, 50s. It was sterile; it was a hospital; It was clean, depending on the owners of the studio, and it all had a very austere feeling. Gary wanted a living room environment and a living room feel, which came with massive acoustic implications that resulted from the insertion of these new materials into a three-dimensional space. 3rd Street was designed with Gary’s wishes in mind, and the acoustic implications of the thing was all very new to me. Remember, in the early days most studios were built for orchestral things, instrumental things, big bands, and so on. They were designed for a definite bandwidth; recordings did not get down into the control of frequencies that went below 40 Hertz, which is basically an acoustic instrument’s bottom end. From my experience in 1965, when we first took over TTG Studios (in LA), our first clients, Eric Burdon and the Animals, and Frank Zappa, loved noise, lots of noise. The music was loud compared to the Basie Band, for example, where, if you stood in the middle of the band the sound was 107, 108,109 dB SPL at the most, and that was a full band at a double forte on the music score. Then suddenly, you had five, or six, or seven rock musicians and you were looking at numbers in the 116 to120 range, generated on that same studio floor with an extended bandwidth of electronic instruments. Well of course, the rooms that were built for the old recordings just couldn’t handle it; they couldn’t get enough control of the sound, particularly of the extreme bottom end. Because Gary wanted his Record Plant on 3rd Street to have a home environment, we were now talking about hardwood on the floors, some hardwood on the wall just as you’d find in a home, perhaps some block, some tinder blocks, bricks, and fabrics, and mirrors representing the windows. And, of course, at the same time you had the drive towards tighter and tighter control of the microphone. At the same time, you had isolation rooms that had to have some kind of real direct vision into the studio so that you could see the band one-on-one as well as see the engineer and producer on the other side in the control room. That’s when we introduced sliding glass doors between control rooms and studios in 3rd Street in 1969 so that they could open it up and use it as an open room, or close it off as an isolation room. The acoustic treatment on the ceilings was just an open weave fabric situation. In those days, not much was known about trapping and treatment of frequencies and so forth. And, of course, we didn’t know much about room geometry, the ratios with length to height. The lighting, well, that had to go incandescent in those days and that was put on dimmers so that you could set a mood up in the room and make it comfortable for the musicians. It was all about mood, environment, relaxation for the creative musicians and their creative ideas.

Chris Stone: Not to mention the 25-cent beer.

Tom Hidley: This was all Gary, and you know what? We built him all of the stuff that he asked for and sat back and just wondered — is this really going to work? We had the L.A. opening party and the conclusion was sensational. Chris, you can speak to the bookings, the type of artists and the quantity of bookings that took place there in 1970,

Chris Stone: Yeah. We were booked for three months on the day we opened in LA.

Tom Hidley: The studio world liked it, and you know what? They copied these concepts in the US, Europe, UK and Asia. Look around the world; everything that is comfortable in the room environment of today is because of Gary’s forward thinking.

Chris Stone: What were you doing before we hooked up at the Record Plant?

Tom Hidley: Immediately before Record Plant I was involved with Ami Hadani at TTG. We both had previously worked together for Phil Ramone at A&R Studios in New York on 48th Street, with Don Frey, who was his partner, and Art Ward who was pretty much the owner. That was a hell of a learning experience, both in tape machine operations and refinements, getting the old Ampex 351s and 350s to be able to be intercut from the first of the reel to the back end of the reel and still maintain constant pitch. A lot of tricks had to be pulled off – and Phil and Don were great at letting me experiment, encouraging me to try this, try that, and sure enough things worked out very well for them. Prior to that, I was with MGM in New York with the famous Val Valentin who was Director of Engineering for Verve and MGM for years. Val was the engineer for Nat Cole, he engineered early Frank Sinatra stuff, Ella Fitzgerald and the Norman Granz library. It was all a very good experience, very musically rewarding. That was my era.

Chris Stone: Tom, could you talk about your speakers…how did they first get designed?

Tom Hidley: That all started back in New York with Phil Ramone. We had speakers at A&R that were the standard studio stuff of the era that only went down to about 63 Hertz. Phil kept saying that something wasn’t right on the bottom end and he was right. Acoustic instruments require 40 Hertz at the bottom end for monitoring and if you truly want to hear the fundamentals of bass drum, the acoustic bass with a bow, you need your monitoring system to allow all that to happen and to be realized. You can’t do it if your speaker stops at 63 Hertz. You don’t hear 50, you don’t hear 40, you don’t hear 45, all that information is gone. When I got to TTG in Los Angeles they had a spate of monitors that were similar to what they had at A&R. Ami (Hadani) said to me, “Are you going to follow through on this monitor thing?” To which I said, “We have to, we really have to. Especially in a room of this size, we’ve got to. You’re going to have low frequencies laying around in the room.” I knew all that from my days at JBL. I had worked for JBL for seven years in the 1950s and I knew a little bit about how rooms responded to sound. Ami asked, “All right, how do you want to start it?” I said, “Well, you’ve got to increase the speaker box volume, you’ve got to add a second woofer to it, that’s where I began, and perhaps we should turn the monitor vertically. How about two woofers, just one active, one passive, or both active in parallel, and we can energize that, and put the tweeter, a driver in range above or the middle between the woofers. Let’s experiment.” Ami said, “All right, fine, go ahead.” So, we did. I didn’t really have any sophisticated equipment for testing and listening. Seat of the pants, we put together our first monitor, and, yeah, it got down to 40 Hertz, actually 38 Hertz. Then I said, “All right, let’s do this,” so we hung them up. And sure enough, it really did work. It was a vast improvement, instantly. It was a small industry in those days. Someone would pick it up the phone and say, “Hey, have you heard this? Have you heard about what’s going on over at TTG?” The news in the industry traveled fast in those days. The guys picked up the phones, as maintenance people often do, as the owners do, and as the producers do, and they talked to their friends on the other side of the nation. LA talked to New York all the time, New York talked to Nashville. People were coming from different parts of the country to hear what we had. We had people in there from the south, musicians from Louisiana, from Alabama, and from Nashville, and we had New Yorkers in there too. Of course, everyone in LA was becoming aware that things were changing. Among the people who came through TTG in those days was Jimi Hendrix who, I think, was the one who originally told Gary about the monitors we had built.

Chris Stone: Meanwhile back at the Record Plant…it all started out as a practical joke. Our biggest customer in those days was Bill Szymczyk who was working with Joe Walsh and the James Gang, and he would say, “Well, gee, how many monitors should we blow up tonight?” It became a competition between Szymczyk and Kellgren. Kellgren came to you (Tom) and said, “Design me something that Szymczyk can’t blow up.” I think I remember Kellgren, probably the first weekend that Szymczyk was there with your brand-new monitors. Gary just kind of sat around doing nothing. And, after about an hour, he looked at Bill and said, “What’s the matter? Can’t you blow them up?” Of course, he couldn’t. That made the Hidley monitor famous from day one.

Tom Hidley: That could have only happened because you found the funds to allow us to go buy the B&K equipment and to hire the contractors who built the roof test platform.

Chris Stone: What other projects did you get involved in with Kellgren?

Tom Hidley: After about six months of operation, Gary came into the shop and said, ” You know, at very high levels of monitoring, my ears begin to hurt, there’s kind of a ringing.” So, I went in control room A, measured the exact material that he was listening to, and the area that began to bother him and me as well — we both noticed it at the same time – was 112.dB/SPL. All I had to do was turn it down a couple of notches and it was all fine. At first I thought something in the speaker system was breaking down electronically. The electronics chain was measured carefully for headroom and within its specifications by a large order of magnitude. Everything was fine. Ultimately, after scratching my head for a long time, I had to come back and say it was all room acoustic design that was introducing these abnormalities, which were not very pleasant at extreme high levels. Gary defined the problem; he was correct once again. From 1970 to 2008, 38 years and 900 studios built and tested, I worked on the problem of Gary’s ear pain that began in 1970. It took me 38 years to get there, and now we’re at a point that 120 dB SPL can be clean, can be acceptable, and can be enjoyed by people without any pain. And Gary put me onto this. Even though it took many years, it would never have been achieved without Gary originally pointing me in that direction.

Chris Stone: How did you start building tape machines?

Tom Hidley: You recall in the late-sixties the industry was eight- track; there was an endless demand for more tracks; the more engineers used track bouncing to compensate for more tracks, the more the noise would go up. There was 12- track one- inch in those days, but the separation track wasn’t very good; you would have high-frequency bleed from one track to another. The only answer was to double the tracks (8-to-16) and widen the tape (1-to-2 inches). It was more mechanics than electronics and it was going to take some time. Eight months later, TTG had the first working 16-track two-inch machine in Los Angeles. To take an Ampex 300 transport, which was designed for the weight of a half-inch reel of tape, and take that up to two-inch, required substantial changes in the transport. Those were done one-by-one-by-one during that eight-month learning curve until finally I got it right. All I needed then was some two-inch tape. So, I called Jim Mullins at 3M and explained what I was doing, that I was interested in the acetate more than the mylar because of the stretch problems; especially on a two-inch format, mylar was just too unstable; especially in the rough handling in the studio environment, the acetate made more sense; at least you could splice it if it broke. I sold Mullins on the idea that the industry was crying out for more tracks and that the only way to give that to them was with two-inch tape, which would first give us 16- track and possibly 24-track.

Chris Stone: Was that the machine you built for us over at Record Plant?

Tom Hidley: Yours came later with the advent of MCI’s two-inch transport. Their electronics was a slice above what I could get out of Ampex.

Chris Stone: I remember Kellgren trying to convince me to hire you, because you were the guy who could give us more billable tracks. Plus, the monitors that even Szymczyk couldn’t blow up.

Tom Hidley: It was an interesting time. When we first got the 16-tracks running, the three machines, two recorders and one player, over at TTG in 1968, I remember Wally Heider, who was a friend and who was then doing all the remotes in town, said to me, “Tom, I’m losing my clients. They’re going to you guys and you lock them up because of your 16- track. It’s not fair.” I said, “So, what do you want?” He said, “Give me two recorders and a player right now.” A month and a half later, we got Wally those three machines. And it spread from there. Then of course, Record Plant had the first 24- track in town.

Chris Stone: We made a lot of money with that machine.

Tom Hidley: That was all a result of the engineers, and Gary was certainly one of them, saying: “Give me more tracks.” You know, in the end, I come back to Gary starting all this. He was behind all these innovations that ultimately everybody wanted.

Chris Stone: Gary liked to give Tom challenges.

Tom Hidley: When you say challenges, Record Plant New York comes to mind. I remember we had a weekend there of 72 hours with no sleep. Impossible job. There was a group of us who just didn’t go home; the studio needed to be up and running Monday morning. A local deli delivered the steaks. Nobody left the building. 72 hours and we did it. The modification was extensive. It was carpentry, it was consoles, it was monitors in all three studios.

Chris Stone: It was a lot of money.

Tom Hidley: A lot of work and a lot of money, but yeah, it all happened. Literally, a lost weekend. Talk about getting on the airplane and dying all the way back to LA.

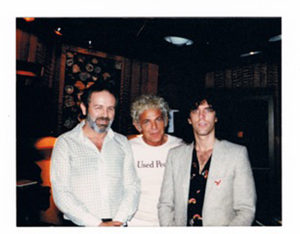

Chris Stone, Tom Hidley, and Ron Nevison.