While Gary Kellgren was scouting locations in Sausalito, living on a houseboat they had rented, Chris Stone was commuting back and forth to run both studios in Los Angeles and New York, and working on a business plan to buy Warner out.

Chris Stone on Third Street in front of Record Plant LA.

On one of his many cross-country flights to New York, Stone grabbed a copy of Rolling Stone off the newsstand at LAX to learn a few things about the record business before meeting up with the clients and staff back in New York. On that trip in late-spring 1972 there was an article that grabbed his attention:

N.Y. Recording Scene Seethes, Sits, Checks Its Books

All does not glisten in the Beau Monde of New York’s recording studios. Business is off 60 percent. Manhattan is the center of the industry but a costly boom in building studios here during the last few years has not met with corresponding enthusiasm to record in them. There are more than 200 studios in the city of New York. Last year, 14 went out of business…Capitol has dropped its million-dollar studio plans and moved its recording operations to LA. RCA and A&R both laid off staff. One big factor is the sheer cost of all the glistening new hardware a top studio needs to stay competitive.

Reading the news while sipping a gin & tonic at 35,000-feet was not what really upset Stone. It was the fact that the Record Plant received a mere mention in the article compared to lengthy descriptions of the goings-on at the other studios around town. The reporter gushed about what Eddie Kramer was doing over at Electric Lady. Media Sound was described as a hotbed of commercial advertising work. Hit Factory was portrayed as the hot, new studio in town. And all the journalist wrote about Record Plant New York was that it was “decorated with the frenzied taste of a whorehouse.”

It was at that moment, with the newsprint rock and roll magazine folded neatly in his lap and a second round on his tray table, Stone realized that Gary was right. He was done with New York too. Stone had enough of the red-eyes and the power struggles with his east-coast chief engineer, and he was determined not to get caught-up in the inevitable, New York City studio business tailspin. With the pilot announcing their descent into Kennedy Airport, Stone knew what he had to do — convince Roy Cicala that “his studio” was his for the taking.

If he wasn’t sure of his decision, his mind was made up once his cab pulled up outside 321 W. 44th Street. Rushing out the building’s front door was a gang of longhairs, pushing one of the bookkeepers wrapped mummy-style with grey-gaffer’s tape to one of the studio’s rolling office chairs, out into the street. The gang of Record Plant staffers were laughing like hippie hyenas as they launched the chair off the sidewalk and into the middle of the street. The girl was petrified, screaming and flailing her arms and legs while strapped to her seat. A car swerved around her as the chair came to a halt. And there, right in the middle of the melee, was Roy Cicala; the man Stone had put in charge of running the New York business was the ringleader, spraying the crowd wildly with fire-extinguisher powder.

The commotion came to a sudden halt when they spotted Stone getting out of the cab. The crowd quickly dispersed back into the building, with Roy standing defiantly with the fire extinguisher in his hands. It was like a scene out of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest where the lunatics had taken over the asylum and Stone was playing the role of Head Nurse. But unlike the others, Roy wasn’t scared of Stone.

Stone ordinarily would have dressed his chief engineer down, but with a bigger mission in mind all he did was shrug his shoulders, grab his valise out of the trunk, head into the studio and go right to work in his corner office. His usual routine was to review the bookings, check receivables and look at the bills. This time he was gob smacked by an invoice from a company named Dolby for $100,000 worth of “noise reduction equipment;” he didn’t know what noise reduction was nor did, but he knew that, with Rolling Stone saying that studios all over town were going belly up, it was an extravagance they couldn’t afford.

Stone tucked the invoice into his breast pocket and walked out of his office to find Roy. He stopped by the studio manager’s desk and glanced at the schedule book, noting that the chief engineer was in Studio A with Blood Sweat & Tears-founder Al Kooper. Kooper was an old friend of Tom Wilson’s from the early Hendrix days who, unlike most of the musicians, appreciated the talents that a hardcore-numbers guy like Stone brought to the business.

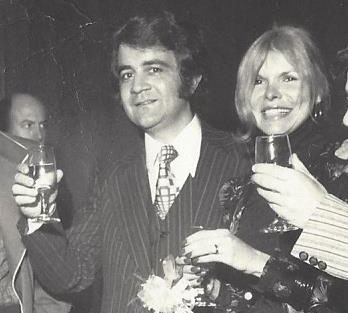

Roy Cicala at the console in Record Plant NY.

When Stone walked into Studio A, Roy was behind the console with Shelly Yakus and their client, Canadian producer Bob Ezrin. Stone looked through the control-room glass and into the studio for Al Kooper but Al wasn’t there. Instead, the studio was occupied by a strange and stringy rock and roller with smudged mascara who was madly conducting a choir of kids.

“Where’s Al Kooper?” Stone asked.

The engineers were smoking a joint, trying to stifle their laughs. Smiling too, Roy introduced his boss to his customer Alice Cooper who was there working on vocals for his album, School’s Out.

“Anyone heard from Al?” Stone continued, doubling down on his mistake.

“I heard he’s down in Atlanta working with a bar band called Lynyrd Skynrd,” someone explained.

Stone nodded his head as if he knew the band and surveyed the studio while the engineers went back to work. The control room was a mess; it looked like a cake fight had just taken place. And even more bizarre, one of the assistant engineers was sitting cross-legged on the floor, handcuffed to a 24-track tape machine.

“What’s with him?” Stone asked Cicala.

Alice’s producer Bob Ezrin snapped the retort: “The kid’s not going anywhere.”

Cicala explained, “We were having trouble with the tape machine until that kid walked in with some tapes, so he’s not going anywhere until we’re done. He’s good luck”

Stone made a mental note to charge the client for the extra service and turned back to Roy to ask, “Wanna grab a bite?”

Cicala’s heavy eyebrows raised perplexed. He and Stone had never socialized outside of the studio before. It was no secret that they rubbed each the wrong way. Cicala knew something was up but answered, “Sure,” turning to his sidekick Shelly to finish the session. “Meet you at Smith’s for a burger at half hour?” he asked, hoping Stone would now leave the room.

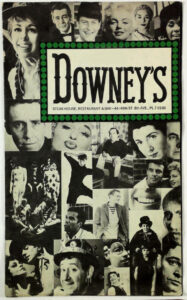

“Make it Downey’s for steak,” was Stone’s reply, referring to the dapper theater-district hangout next door to Smith’s that was usually frequented by the studio’s more affluent “Mad Men” clientele.

Walking down 44th Street alone towards 8th Avenue a few minutes later, Stone was shocked by how much the Times Square neighborhood had deteriorated since he had left for the west coast. Over the past twelve months, New York City had broken a record for murders and rapes and unemployment had reached over one million for the first time. Stone no longer felt safe on the city streets and now was even further determined to get out of town.

Sitting across the table from each other after ordering drinks, Cicala put his boss on the defense right from the start: “So, you guys are fucking me and the rest of the New York team by stealing our ‘bread and butter’ engineer, Tom Flye, huh,”

“Take it up with Tom…he’s had it with New York. Do you see what’s going on out in those streets? Can you blame him?” Then, changing the subject, Stone pushed back even harder: “Quite a side-show you’re running here. What the hell was going on out in the street before?”

Cicala laughed. “Just a bit of innocent fun. Keeps the kids working hard. The clients love it too. It takes off the edge.”

“And what the hell is a ‘Dolby?’” he asked, fishing the invoice out of his pocket and flinging it onto Cicala’s place setting.

“It’s something that makes a hit record,” was Cicala’s response, talking down to the bean counter who didn’t know tech.

“$100,000 sounds like it should guarantee a Grammy, which none of your records won this year.”

“$100,000 is what it takes to stay in business in this town these days.”

“So why did Record Plant New York only get a brief mention in this week’s Rolling Stone?”

“Sorry, I didn’t read the article,” Cicala replied before making it clear that he had enough. “Why are we sitting here Stone…so you can give me shit?”

“No, so I can make you rich.”

“I’m listening.”

Starting with the line from the recently released Godfather movie, Stone began, “Listen Roy, I’m going to make you an offer you can’t refuse. Warner is trying to unload the Record Plant. Gary and I are buying out LA and we’re building Sausalito. New York’s up for grabs if you want it.”

From the look on his face, Stone could tell that Cicala was flattered but unsure. With the help of his martini Stone continued his pitch:

“First, let’s agree Roy that you are a fanatic, you are crazy, you are a masochist and you have decided that your goal in life is to work very hard at just staying alive, with only a very small chance for success…”

Then, just as he was getting started, the waitress interrupted Stone’s rant, delivering two, sizzling sirloins to the table. Cutting into his rare slab of beef with a massive butcher’s knife, and with his eyes on his plate and not on his dinner guest, Stone went in for the kill:

“Roy, you are about to join a very dedicated group of nuts who live for recorded audio and are willing to take almost any chance to be a recording studio owner. Why would you want to work for some shithead like me who is going to tell you what you can and can’t buy? If you own the place you can buy as many damn Dolbys as you like.”

Chris Stone at his desk back in LA.