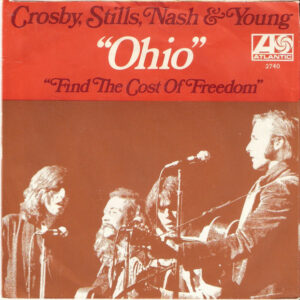

The last time Jimi Hendrix worked at Record Plant New York was May 15, 1970, one week before the Woodstock album’s release and the same date that the shootings at Kent State appeared on the cover of Life magazine. The black & white photographs startled a nation and changed the course of the Vietnam War. David Crosby picked up his own copy of the magazine from a grocery-store newsstand and stared at it in tears before handing it to Neil Young whose response was to grab a guitar, walk out into the woods, and write “Ohio,” one of the greatest protest songs of all-time. In his biography, Wild Tales, Graham Nash remembers what happened next:

“Croz immediately called me and said, ‘We need to be in the studio right now.’

‘What is this all about?’ I asked him.‘It’s a song we’ve got to cut immediately,’ he insisted. ‘Round up the guys…’”

The “guys” were all planning to be together in LA to rehearse for their next tour, while Stills was already down there working on his first solo LP at Record Plant Studio A with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (CSNY) engineer Bill Halverson behind the console.

CSNY wasn’t a Record Plant client, though their first session as a band took place at the Record Plant New York. Once out in LA, the band preferred the more low-key Heider’s Studio Three, which had originally been built for the Beach Boys to evade their corporate overseers over at Capitol. In comparison to the Record Plant, which had already become a scene, Nash recalls, “Heider’s was a beautiful little dump of a place. We recorded there because it was private, off the beaten track.”

Unfortunately, Heider’s Studio Three was booked the night of the “Ohio” session, so they used Stills’s time over at Record Plant Studio A instead. Halverson rented one of his favorite 3M 24-tracks from Heider, raided the Record Plant microphone closet for an expensive German vocal mic, and hired them a new rhythm section.

The assistant on the date, Mike D. Stone, remembers, “They each came into the studio individually. I remember Neil coming in and going into his own corner. Graham Nash came into the control room and introduced himself; he was probably one of the few musicians that ever did that to me. They all seemed so isolated from each other, until they sang.”

“The mood was very intense,” Halverson adds, “I’ve been around those personalities for a long time, and the four of them take over a room. That night they were bent on getting it right and were on a mission. We set up and they fiddled around for a while, and I don’t recall us doing more than two or three takes of the song with live vocals, live harmonies and everybody chiming in.”

The band picked “Find the Cost of Freedom” for the B-side and, to record the song, Halverson arranged four, facing folding chairs inches apart, with one mic set up for Stills’s guitar. They did a few quick takes, Halverson doubled their voices, applied filtering to even it all out, and had a master track finished in less than a half hour. Together, they “gang mixed” both songs on the studio’s Hidley speakers and had the entire single done by dawn.

Coincidentally, Atlantic Records President Ahmet Ertegun was in Los Angeles and stopped by the Record Plant for a listen. Graham Nash tells the rest of the story: “’Listen, man, we want it out now,’ we told him. ‘This is too big a deal. The country has started shooting its own children.’

‘But you’ve got “Teach Your Children” going to number one,’ he said.

‘Pull it!’ I told him.

Ertegun was incredulous. ‘Graham, you’re going to have a number-one hit!’

‘I don’t care. Pull it.’”

In less than two weeks, the song hit the FM radio airwaves. “Ohio”, along with Jimi’s “Star Spangled Banner,” amped up the anti-war movement in America that summer. With Jimi finally out of Record Plant NY, working exclusively at Electric Lady for the remaining months of his life, a band of anti-war demonstrators late-one-night rappelled off the 10th floor roof and raided the Selective Service records office on the floor below. Nobody ever found out who at the Record Plant let them in.